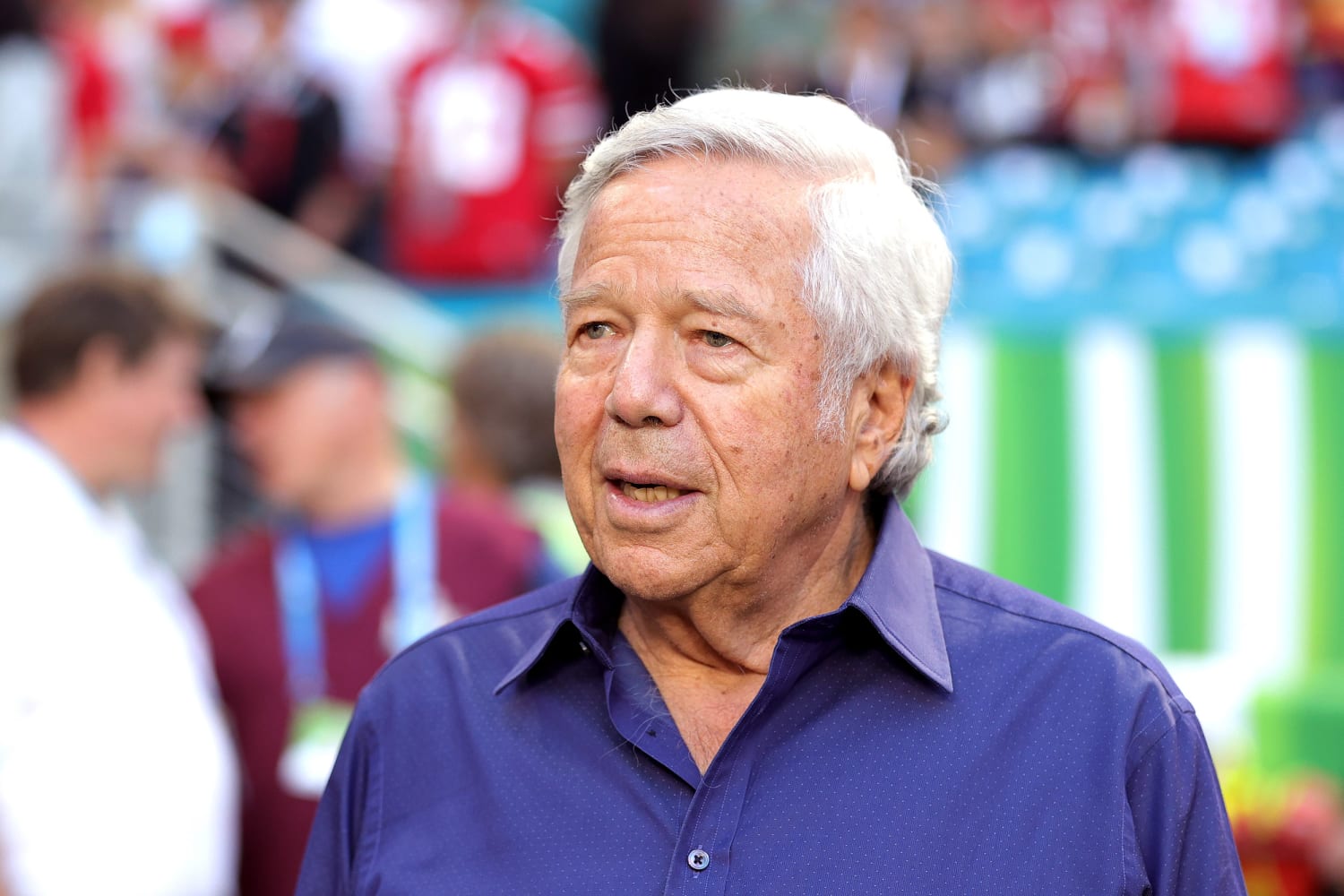

Here's a great article by accomplished writer May Jeong in Vanity Fair about the infamous bust involving the Asian massage parlor, Robert Kraft and "sex trafficking" allegations. The writer does a great job countering the reckless lies told by the various law enforcement agencies involved in the bust (local police, U.S. Homeland Security and ICE). Isn't it great to know that people from Homeland Security are spending weeks and months worth of time busting poor immigrant women for giving massages and handjobs to men?

Robert Kraft is a hero (and I say that as someone who hates the Patriots). His decision to fight the charges ultimately allowed a writer like Jeong to dig into the story and find the truth. Here's a brief excerpt from a long article (bravo to Vanity Fair for publishing it during the current moral panic about everything related to sex).

“YOU WON’T BELIEVE WHAT HAPPENED”: THE WILD, DISTURBING SAGA OF ROBERT KRAFT’S VISIT TO A STRIP MALL SEX SPA

After the Patriots owner made two trips to Orchids of Asia Day Spa, where a half-hour “massage” costs $59, he was charged with soliciting a prostitute. What happened next was not what anyone expected.

vanityfair.com

vanityfair.com

BY MAY JEONG

NOVEMBER 2019

...The raids on Orchids and other massage parlors in South Florida were conducted in the name of rescuing women from sex trafficking. But the only people put in jail were the women themselves. A few, like Lulu and Mandy, managed to post bail and were placed under house arrest. But others were transferred to the custody of ICE. Women who migrated to America in search of work—who chose the least bad option available to them—were being punished for what one of their lawyers calls “the crime of poverty.”

The New York Times and other news outlets, quoting investigators, initially presented the raids as a clear-cut case of sex trafficking. Women at the spas, the media reported, were working “14 hour days” and “sleeping on massage tables.” After “surrendering” their passports to spa owners, they were not allowed to leave the premises without an escort. The “wretched” women in “strip-mall brothels” were not sex workers, but rather “trafficking victims trapped among South Florida’s rich and famous.”

But as police subjected the women to hours-long interrogations, those claims began to unravel. The only woman alleged to have been locked up and forced to live on the premises was Yong Wang, who went by the spa name Nancy. In fact, like many other employees, Nancy had been hired from out of state, so her boss drove her back and forth from the job. When the owner fell ill, Nancy was asked if she wouldn’t mind sleeping at the spa.

The one woman whose passport had allegedly been taken away was Lixia Zhu, or Yoyo. During questioning, the police repeatedly grilled Yoyo, looking for evidence of human trafficking. Did anyone else set up her bank account for her? Did anyone else have access to her account? “Did you feel like you had a choice to come down and work, or did you feel like you were forced to?”

“No one forced me,” Yoyo insisted. It was the terrible winter of 2018 back in Pennsylvania, where she was living at the time, that inspired her to move to Florida.

The interrogator pressed harder. “Did you feel like you had to do this?”

Yoyo shook her head.

“Then why did you do it?”

The inquiry continued along these lines for several more hours. It was somehow easier for law enforcement officers in South Florida to believe that the women had been sold into sex slavery by a global crime syndicate than to acknowledge that immigrant women of precarious status, hemmed in by circumstance, might choose sex work.

In the end, Yoyo told police that her boyfriend had confiscated her passport, locked it in a safe, and threatened her with a gun. He was the one, she intimated, who had forced her into sexual slavery.

Later, during a hearing conducted after she had managed to retain a lawyer, Yoyo recanted the story about her boyfriend. She told the court that she had said what she felt the police wanted to hear, in the hopes of getting a lighter sentence.

Within weeks of the raids, the state’s case had evaporated. There was no $20 million trafficking ring, no women tricked into sex slavery. The things the state had mistaken as markers for human trafficking—long working hours, shared eating and living arrangements, suspicion of outside authorities, ties to New York and China—were, in fact, common organizing principles of many Chinese immigrant communities. As an assistant state attorney in Palm Beach told the court on April 12: “There is no human trafficking that arises out of this investigation...”

Robert Kraft is a hero (and I say that as someone who hates the Patriots). His decision to fight the charges ultimately allowed a writer like Jeong to dig into the story and find the truth. Here's a brief excerpt from a long article (bravo to Vanity Fair for publishing it during the current moral panic about everything related to sex).

“YOU WON’T BELIEVE WHAT HAPPENED”: THE WILD, DISTURBING SAGA OF ROBERT KRAFT’S VISIT TO A STRIP MALL SEX SPA

After the Patriots owner made two trips to Orchids of Asia Day Spa, where a half-hour “massage” costs $59, he was charged with soliciting a prostitute. What happened next was not what anyone expected.

vanityfair.com

vanityfair.com

BY MAY JEONG

NOVEMBER 2019

...The raids on Orchids and other massage parlors in South Florida were conducted in the name of rescuing women from sex trafficking. But the only people put in jail were the women themselves. A few, like Lulu and Mandy, managed to post bail and were placed under house arrest. But others were transferred to the custody of ICE. Women who migrated to America in search of work—who chose the least bad option available to them—were being punished for what one of their lawyers calls “the crime of poverty.”

The New York Times and other news outlets, quoting investigators, initially presented the raids as a clear-cut case of sex trafficking. Women at the spas, the media reported, were working “14 hour days” and “sleeping on massage tables.” After “surrendering” their passports to spa owners, they were not allowed to leave the premises without an escort. The “wretched” women in “strip-mall brothels” were not sex workers, but rather “trafficking victims trapped among South Florida’s rich and famous.”

But as police subjected the women to hours-long interrogations, those claims began to unravel. The only woman alleged to have been locked up and forced to live on the premises was Yong Wang, who went by the spa name Nancy. In fact, like many other employees, Nancy had been hired from out of state, so her boss drove her back and forth from the job. When the owner fell ill, Nancy was asked if she wouldn’t mind sleeping at the spa.

The one woman whose passport had allegedly been taken away was Lixia Zhu, or Yoyo. During questioning, the police repeatedly grilled Yoyo, looking for evidence of human trafficking. Did anyone else set up her bank account for her? Did anyone else have access to her account? “Did you feel like you had a choice to come down and work, or did you feel like you were forced to?”

“No one forced me,” Yoyo insisted. It was the terrible winter of 2018 back in Pennsylvania, where she was living at the time, that inspired her to move to Florida.

The interrogator pressed harder. “Did you feel like you had to do this?”

Yoyo shook her head.

“Then why did you do it?”

The inquiry continued along these lines for several more hours. It was somehow easier for law enforcement officers in South Florida to believe that the women had been sold into sex slavery by a global crime syndicate than to acknowledge that immigrant women of precarious status, hemmed in by circumstance, might choose sex work.

In the end, Yoyo told police that her boyfriend had confiscated her passport, locked it in a safe, and threatened her with a gun. He was the one, she intimated, who had forced her into sexual slavery.

Later, during a hearing conducted after she had managed to retain a lawyer, Yoyo recanted the story about her boyfriend. She told the court that she had said what she felt the police wanted to hear, in the hopes of getting a lighter sentence.

Within weeks of the raids, the state’s case had evaporated. There was no $20 million trafficking ring, no women tricked into sex slavery. The things the state had mistaken as markers for human trafficking—long working hours, shared eating and living arrangements, suspicion of outside authorities, ties to New York and China—were, in fact, common organizing principles of many Chinese immigrant communities. As an assistant state attorney in Palm Beach told the court on April 12: “There is no human trafficking that arises out of this investigation...”