Coronavirus

- Thread starter C.B. Brown

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Fuck Legault.

He has been an asshole along with Aruda all through this pandemic playing to public opinion only.

I will probably see my sons for Christmas, I haven’t seen them except on FaceTime for months.

He keeps schools open where there are 30 kids in front of every teacher with crowding in the halls sitting very close to each other on buses.

Every large store is full of shoppers but restaurants can’t open.

His half ass attempts are totally useless as can be seen by how the virus is spiking and he still hasn’t learned shit about how to control the virus even in CHSLD where people are not going anywhere or mingling with anybody except staff.

He has been an asshole along with Aruda all through this pandemic playing to public opinion only.

I will probably see my sons for Christmas, I haven’t seen them except on FaceTime for months.

He keeps schools open where there are 30 kids in front of every teacher with crowding in the halls sitting very close to each other on buses.

Every large store is full of shoppers but restaurants can’t open.

His half ass attempts are totally useless as can be seen by how the virus is spiking and he still hasn’t learned shit about how to control the virus even in CHSLD where people are not going anywhere or mingling with anybody except staff.

Fuck Legault.

He has been an asshole along with Aruda all through this pandemic playing to public opinion only.

I will probably see my sons for Christmas, I haven’t seen them except on FaceTime for months.

He keeps schools open where there are 30 kids in front of every teacher with crowding in the halls sitting very close to each other on buses.

Every large store is full of shoppers but restaurants can’t open.

His half ass attempts are totally useless as can be seen by how the virus is spiking and he still hasn’t learned shit about how to control the virus even in CHSLD where people are not going anywhere or mingling with anybody except staff.

And the a-hole has the nerve to say he's made no errors

HuffPost is now a part of Verizon Media

The death rate (per million) is 3x that of Ontario. The infection rate is worst than Ontario but not as much. In other words he continues to fail with the elderly.

I understand the frustration. If you play safe the odds are low. But on the other hand, January is going to be a shit-show in the hospitals and we are a few months away from the beginning of the end. Be safe !

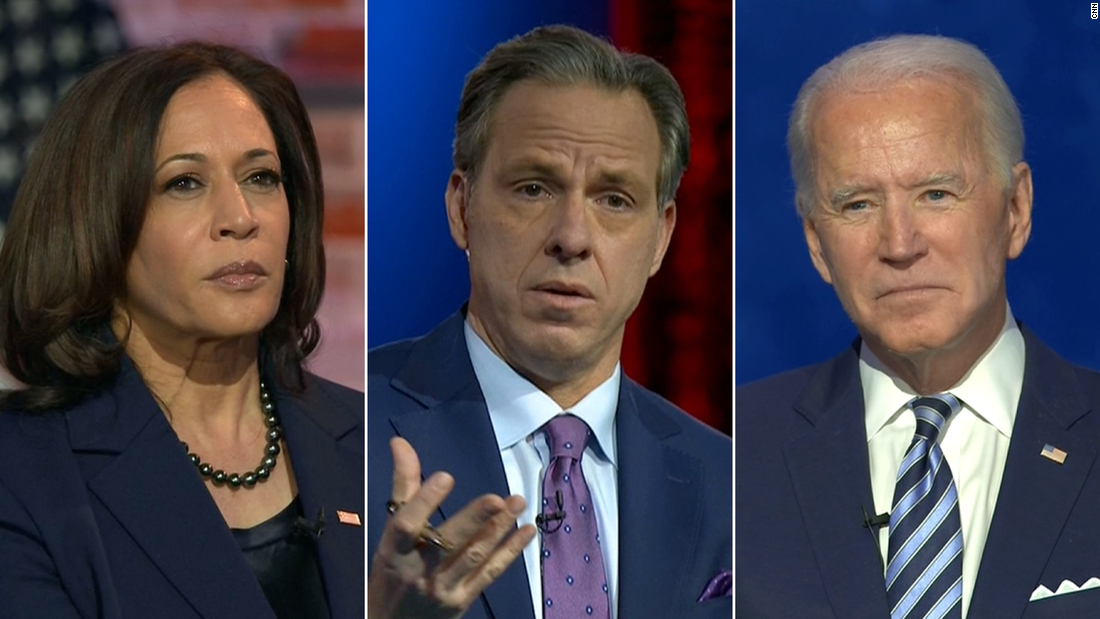

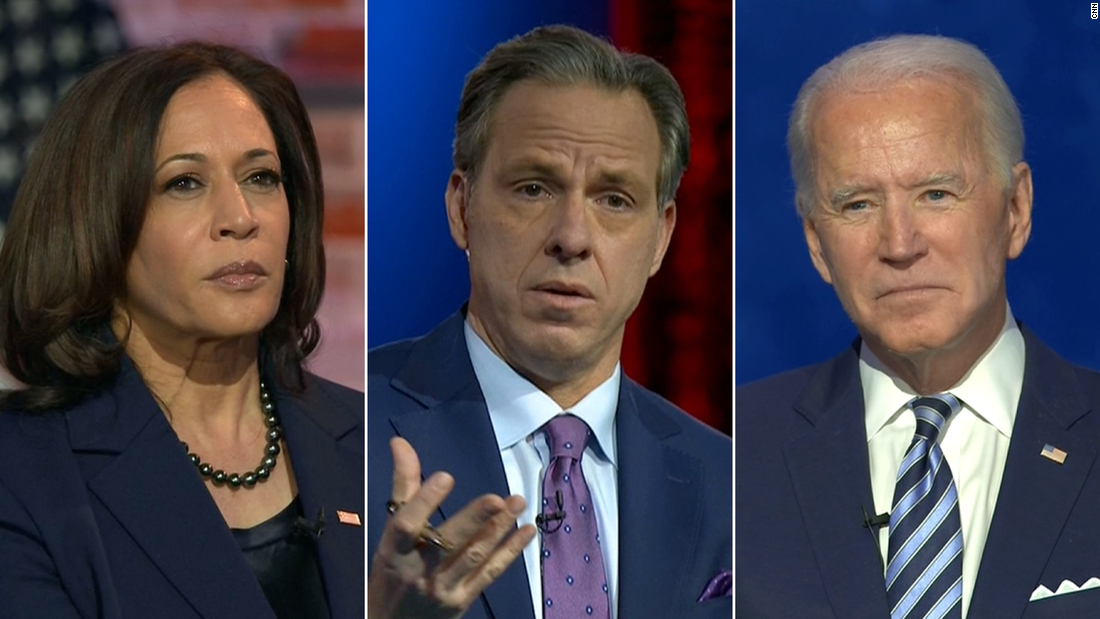

Biden: Fauci is Da Man; Masks To Be Worn for 1st 100 days

www.cnn.com

www.cnn.com

CNN Exclusive: Biden says he will ask Americans to wear masks for the first 100 days he's in office

President-elect Joe Biden told CNN's Jake Tapper on Thursday that he will ask Americans to wear masks for the first 100 days after he takes office, in a sign of how Biden's approach to the virus will be dramatically different from President Donald Trump's response.

Wow what a revelation how on earth did Biden come up with this new concept of wearing a mask.

Did he by any chance receive this wonderful new piece of information from Dr Fauci of all people.

Now that he is saying it I am 100% certain every American is going to comply without question.

Finally they are making America great again.

Did he by any chance receive this wonderful new piece of information from Dr Fauci of all people.

Now that he is saying it I am 100% certain every American is going to comply without question.

Finally they are making America great again.

No right ...it's not a new concept....just a way to SAVE lifes durant cette terrible tragédie  .....and yes HE will listen and work with FAUCI

.....and yes HE will listen and work with FAUCI  ......right not 100% will wear it BUT more more will in the next tough coming months.....that's what i call.... true LEADERSHIP

......right not 100% will wear it BUT more more will in the next tough coming months.....that's what i call.... true LEADERSHIP .

.

What does Biden have to say about Europe, especially Germany, where they wore the masks like their forefathers who wore the Nazi armband and they followed draconian lock down procedures and a massive 2nd wave happened anyway?

everywhere I go people are wearing masks but we have an outbreak anyway. Is the senile old coot sure that they are doing anything? I wear them but I have no idea. I just thank God that lethality of this disease is so low.

everywhere I go people are wearing masks but we have an outbreak anyway. Is the senile old coot sure that they are doing anything? I wear them but I have no idea. I just thank God that lethality of this disease is so low.

Last edited:

I am so glad that all Americans will all now start wearing masks.

It took a forgetful old fart to convince them of this as apparently they are all mindless fools and cannot think for themselves.

Finally they have a leader that just by his word alone will ensure the safety of all Americans.

This is what I call leadership.

It is time they got rid of that crack pot Trump with his warp speed plans that now have 4 viable vaccines ready for approval.

Dont even bother using these vaccines Biden will talk them through what they need to do all they have to do is listen.

It took a forgetful old fart to convince them of this as apparently they are all mindless fools and cannot think for themselves.

Finally they have a leader that just by his word alone will ensure the safety of all Americans.

This is what I call leadership.

It is time they got rid of that crack pot Trump with his warp speed plans that now have 4 viable vaccines ready for approval.

Dont even bother using these vaccines Biden will talk them through what they need to do all they have to do is listen.

I seem to remember Trump listening also when Fauci said he does not recommend masks as that would lead people into a false sense of safety and it may just be even worse to wear a mask.....and yes HE will listen and work with FAUCI......right not 100% will wear it BUT more more will in the next tough coming months

I guess you just need to wait with Fauci eventually he may just get it right and he might even tell you the truth of course you need to guess which is right and when he is telling the truth.

Yep. The guys has flip-flopped on everything.

The Dems may come up with an alternative. Either you wear a mask or you put one of those virtue signaling signs in your front yard that says “In this house we believe...”

The Dems may come up with an alternative. Either you wear a mask or you put one of those virtue signaling signs in your front yard that says “In this house we believe...”

Fauci knew that masks work even when he told the public that they don`t.

He was trying to save the existing limited supply for health care workers.

China was buying up the world`s supply and Fauci was afraid of a toilet paper type run on masks by the public.

This was a hard decision with no good ending.

Now that there are enough masks everyone is encouraged to wear one by Fauci and every sane person. Only fools and those with a political agenda, don`t follow the science.

He was trying to save the existing limited supply for health care workers.

China was buying up the world`s supply and Fauci was afraid of a toilet paper type run on masks by the public.

This was a hard decision with no good ending.

Now that there are enough masks everyone is encouraged to wear one by Fauci and every sane person. Only fools and those with a political agenda, don`t follow the science.

The old I only lied to protect you and it was for the good of everyone concerned.

It has a tendency to come back and bite you in the ass.

He stood along side of Trump many times and you could see it on his face that he was cringing at some of the things being said yet like a good little bobble head doll Fauci several times stepped up to the plate and nodded his approval.

I stopped having any kind of respect for him after that.

It has a tendency to come back and bite you in the ass.

He stood along side of Trump many times and you could see it on his face that he was cringing at some of the things being said yet like a good little bobble head doll Fauci several times stepped up to the plate and nodded his approval.

I stopped having any kind of respect for him after that.

Fauci lies about wearing masks but is given a pass and a new job at the Whitehouse. The president downplays the virus to prevent panic in the streets and it’s impeachment part 2.

The country has had enough of both of them. I think Fauci continuing in his role is a mistake. Washington is cleaning house, so they should clean house and let Fauci go back to his private practice. His over exposure and daily cable news interviews are played out. Biden is not clever enough to find someone new so maybe he can bring back someone from the Obama administration like all of his “original” cabinet picks.

The country has had enough of both of them. I think Fauci continuing in his role is a mistake. Washington is cleaning house, so they should clean house and let Fauci go back to his private practice. His over exposure and daily cable news interviews are played out. Biden is not clever enough to find someone new so maybe he can bring back someone from the Obama administration like all of his “original” cabinet picks.

It’s ok for kids to go to school again. Now quick. Get to school before he changes his mind again.Fauci lies about wearing masks but is given a pass and a new job at the Whitehouse. The president downplays the virus to prevent panic in the streets and it’s impeachment part 2.

The country has had enough of both of them. I think Fauci continuing in his role is a mistake. Washington is cleaning house, so they should clean house and let Fauci go back to his private practice. His over exposure and daily cable news interviews are played out. Biden is not clever enough to find someone new so maybe he can bring back someone from the Obama administration like all of his “original” cabinet picks.

The president downplays the virus to prevent panic in the streets and it’s impeachment part 2.

If you believe that that's why he downplayed the virus, then I have some great land in Florida to sell you. PM me.

Did we see panic in the streets in other places where the leaders were more honest?

You downplay on my comment but you have nothing to say about it yourself. None of the leaders were more honest. If they were, I’m sure you would have posted about it. The more important part of my post was about Fauci and that’s where I drew my comparison from. But you chose to miss my point entirely with a cute, witty comment about selling me a property in Florida.If you believe that that's why he downplayed the virus, then I have some great land in Florida to sell you. PM me.

Did we see panic in the streets in other places where the leaders were more honest?

You downplay on my comment but you have nothing to say about it yourself. None of the leaders were more honest. If they were, I’m sure you would have posted about it. The more important part of my post was about Fauci and that’s where I drew my comparison from. But you chose to miss my point entirely with a cute, witty comment about selling me a property in Florida.

I still have that property if you're interested.

For 1 example, see: Germany.

I haven't posted more about it, or other leaders and their reactions because... why would I? I'm not as sure as you are that I would have posted about it.

Again, completely missing my original point which had nothing to do with what your talking about.I still have that property if you're interested.

For 1 example, see: Germany.

I haven't posted more about it, or other leaders and their reactions because... why would I? I'm not as sure as you are that I would have posted about it.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 61

- Views

- 11K

- Replies

- 70

- Views

- 38K

- Replies

- 251

- Views

- 45K

- Replies

- 108

- Views

- 22K