The latest environmentalist

fad is to ban gas stoves, with the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission now doing a study on their ill effects (and a commissioner saying a ban on their import and manufacture is on the table). The agency's rationale is that such stoves degrade indoor air quality. The pushback has been severe given that any self-respecting cook would rather heat up a frozen dinner in the microwave than pan-fry dinner on an electric burner.

Gas banners have touted studies showing that gas cooking exacerbates asthma—although a properly vented

stove hood minimizes the risk. The main push behind this moral panic comes from

climate-change worriers, who are intent on reducing the nation's carbon footprint. Some cities already are imposing moratoriums on natural gas.

What does this have to do with today's topic of water policy? One gets a sneaking suspicion that with any resource issue the environmental up-lifters are more interested in disrupting our lifestyles than solving actual environmental issues. The real climate threat comes from

developing nations—not high-end gas stoves in suburban American households.

Likewise, some targeted investments could solve the state's water issues—by bolstering our water-storage capabilities, building desalination facilities, recycling water, improving groundwater recharge basins, and promoting water trading. California now faces a budget deficit, but last year we had a $97.5-billion surplus. A small

portion could have fixed the problem for decades.

Instead, many California environmentalists prefer

water rationing—with the goal of forcing us to use much less water even though we've vastly reduced our per-capita water usage. Conservation is good, but the end goal should be assuring plenty of water for our homes and businesses rather than forcing the public to do penance. Am I the only one who thinks our policymakers want us to suffer?

California has endured weeks of pounding rain, with 90 percent of the population facing a

flood watch. Here in the low-lying Sacramento area, rising waters and bursting levees have washed out roads, destroyed homes, and taken lives. My community has at times become an island, with flooded roadways cutting access to town. We've lost electricity and were required to evacuate.

Many pundits blame climate change. Yet flooding is nothing new in the Golden State. During the great flood of 1862, historical

reports say that a lake 300 miles long and 20 miles wide formed in the Central Valley. Gov. Leland Stanford rowed his own boat to his inauguration. Environmentalists love catastrophe—and they

predict that the state is at risk of another similar flood.

Just months ago, as we suffered through another grueling drought, some environmentalists claimed we were entering a

mega-drought that could last a century and turn the entire West into a dust bowl. They should make up their mind.

Drought or floods, excessive heat or cold—it's all

climate change to them, even though Mother Nature has brought varying weather patterns since, well, forever. I'm not denying that we're facing a changing climate, but the doomsayers seem a bit too eager to use the latest weather event to justify their goals of changing the way we live.

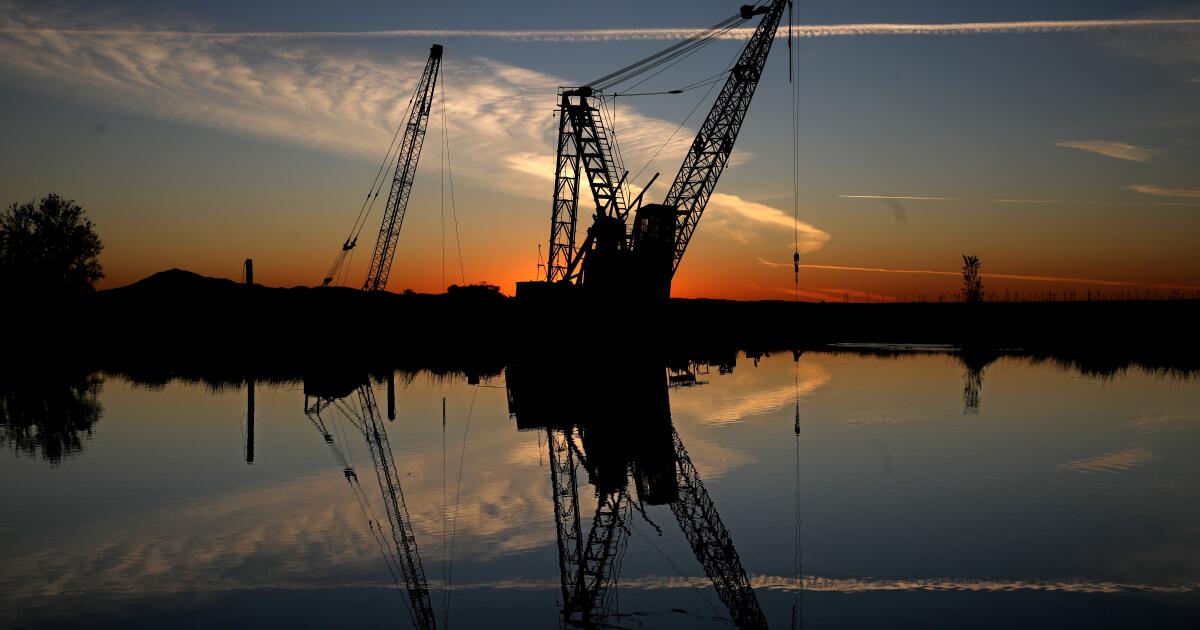

The key reason California has yet to experience another 1862-style flood is obvious: In the 20th century, California dammed its major rivers, built giant dams, reservoirs, and a system of canals. They turned the state into a giant

plumbing project. The State Water Project and Central Valley Project didn't only provide water for a then-growing population, but served as massive flood-control projects.

That's resulted in some environmental problems, but it's allowed nearly 40 million people to live here. Our water systems are engineering marvels, even if the state hasn't maintained them or

expanded them to accommodate a doubled population. The obvious answer is to build upon a previous generation's legacy rather than hector us into using less water (when it's dry) or accepting floods (when it's wet).

Despite the recent atmospheric river, most of California still is officially experiencing

drought conditions. The reservoirs are

filling up, yet they remain below historical averages. It takes a long time to plan water infrastructure, navigate the environmental-impact hurdles, and build it. Unfortunately, if the recent past is a guide our state's leaders will breathe a sigh of relief at the rains, do little or nothing, and then bloviate about climate change after the next drought takes hold.

Meanwhile, environmentalists will do what they always do: warn us about catastrophe and prepare us to endure years of unpleasantness. CNN

quoted climate scientist Peter Gleick: "We have to let our rivers flow differently, and let the rivers flood a little more and recharge our groundwater in wet seasons. Instead of thinking we can control all floods, we have to learn to live with them."

So just get used to the evacuations. Or get used to rationing water. And you better give up those gas stoves and gas-powered

lawn equipment or whatever. To some of us, these are solvable problems, but to others they're the latest excuse to make us miserable.

www.forbes.com

www.forbes.com